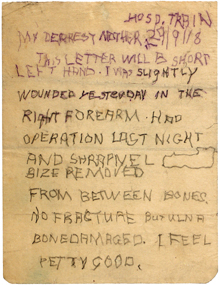

The day after his right forearm was “slightly wounded,” Captain Frederick Banting used his uninjured left hand to pen a wobbly note home, while on board an ambulance train travelling to No. 20 General Hospital, in Camiers, northern France. The letter assures his mother that despite his wound he is doing well. The tendency to downplay injuries and hardships was commonplace among First World War soldiers. Like many of his U of T comrades, Banting refused to discuss his injuries publicly, believing it was unseemly to complain or to brag.

Banting, who would become one of the world’s most celebrated medical heroes, was a member of the Class of IT6, which also included Dr. Norman Bethune who would likewise capture the world’s attention for his humanitarian medical service. Although keen to enlist, Banting was twice rejected on account of his poor eyesight. Undeterred, he tried a third time and was finally accepted into the Canadian Army Medical Corps. He served first as a medical officer in the Amiens-Arras sector and later as medical officer with the 4th Canadian Division near Cambrai.

Banting was wounded in late September 1918, just weeks before the end of the war. In spite of his injury, he continued treating other wounded patients and was awarded the Military Cross for bravery and determination under fire. He spent his convalescence in England studying for the examinations of the Royal College of Surgeons and returned to Toronto in 1919, taking up a post at the Christie Street Hospital for Veterans. By the fall of that year he had fully recovered from his wound and began a surgical residence at the Hospital for Sick Children with a specialty in orthopaedics. It was in 1921 that Banting’s place in history was assured when, together with Charles Best and others, he discovered insulin, a groundbreaking treatment for diabetes that earned Banting the Nobel Prize in Medicine.