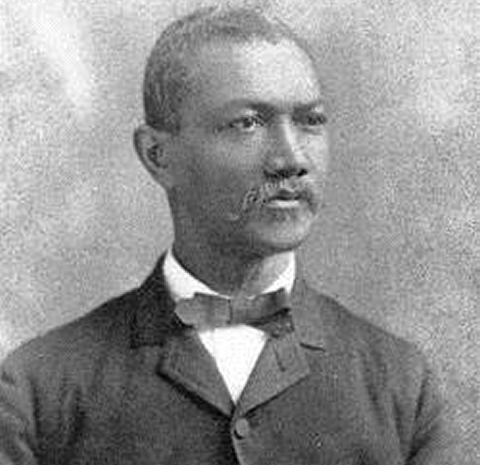

Almost a century before Rosa Parks defied Alabama’s racial segregation laws, Trinity graduate Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta refused to give up his seat in the “whites only” section of a Washington DC streetcar. Dressed in his U.S. Army officer’s uniform, Augusta was physically ejected from the streetcar. He railed against this injustice in letters to newspapers and government officials. In 1865, a year after the incident, Congress decreed that all streetcars in the nation’s capital were to be desegregated.

This was neither the first nor last time Augusta would challenge the discriminatory practices of his native country. Denied entrance to American medical schools on the basis of colour, he was granted admission to Trinity Medical College in the early 1850s, becoming the first black medical student in Canada West.

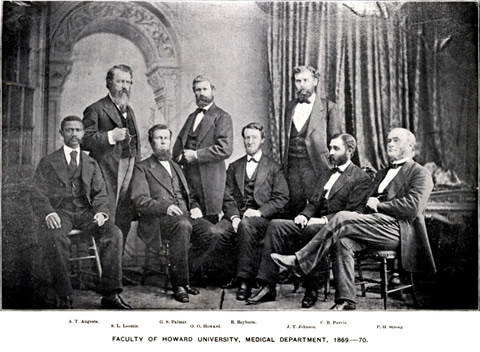

Augusta excelled at Trinity, so much so that U of T president John McCaul publicly acknowledged his superior intellect. Augusta took particular interest in anatomy, taught by Dr. Norman Bethune (namesake and grandfather of the more famous Dr. Bethune ). Augusta would later go on to teach anatomy for almost a decade at Howard University in Washington, as the first black professor of medicine in the United States.

During and after graduating with a Bachelor of Medicine degree in 1860, Augusta worked for several years as a physician in Toronto, where he became a leader in the black community. He offered medical care to the poor, founded a literacy society that donated books and school supplies to black children and was active in antislavery circles on both sides of the border.

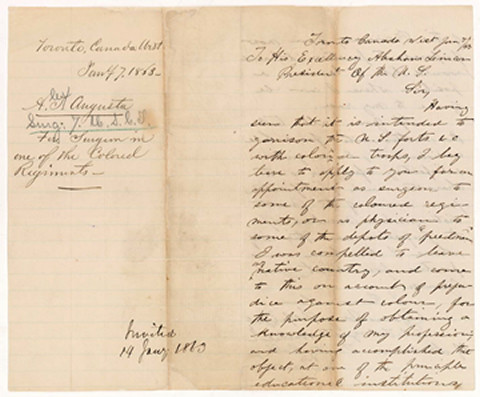

Despite his success in Canada, with war raging south of the border, Augusta felt duty bound to use his medical training in support of “my race.” On Jan. 7, 1863, less than a week after the Emancipation Proclamation authorized black men to serve, Augusta wrote to President Lincoln requesting to be appointed as a physician to the newly created “colored regiments” in the Union Army. (In an odd twist of fate, two years later, Augusta would lead a procession of 75,000 “colored troops” through the streets of Baltimore as President Lincoln’s body passed though the city.)

In April, 1863 Augusta became the first African-American commissioned as a medical officer in the U.S. Army (at the rank of major) and one of only 13 to serve as surgeons during the war. Within two years, Augusta was promoted to lieutenant colonel and became the highest-ranking black officer in the U.S. military.

Augusta mustered out of service in 1866, and for the next quarter century he remained active in the Washington DC medical community, variously working in local hospitals, private practice and as a university professor.

Despite his many accomplishments, however, Augusta and other black doctors were refused admission to the local society of physicians. Unsurprisingly, Augusta fought back—all the way to Congress—but never gained entry into the DC medical society. On January 15, 1870, Augusta co-founded the National Medical Society of the District of Columbia, which accepted black and white members.

Augusta also crusaded to desegregate DC’s regional transit system. When brutally attacked by white passengers—who objected to a black man in an officer’s uniform—on a Baltimore train, Augusta again took his story to the press. In a letter published in multiple newspapers, he asserted his right as a Union officer “to wear the insignia of my office, and if I am either afraid or ashamed to wear them, anywhere, I am not fit to hold my commission.”

Several years later, Augusta testified before a Congressional Committee on behalf of his patient Kate Brown, who was seriously injured when she was forcibly ejected from the “white people’s car” on a train bound for Washington. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court; the 1873 Railroad Company v. Brown decision ruled that white and black passengers must be treated with equality in the use of the railroad’s cars.

Dr. Alexander T. Augusta died at home four days before Christmas, 1890. Even in death Augusta broke the colour barrier. Interred with full military honours, he became the first black officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

No Responses to “ Doctor of Courage ”

Really interesting article about a fascinating man. I have to confess, I didn't know about him and it's remarkable to think that he was trying to desegregate public transit a hundred years before Rosa Parks!

Great article, Alice. So many firsts! Is it likely that Augusta Ave. in Toronto (running through Kensington Market and Alexandra Park) is named after him?

I am proud at what this man has accomplished for all of humanity, and my own college's welcoming of him. We need more humanitarian spirits that he was so imbued with. And yes, I wonder if Augusta Ave. was christened in his honor.

Alice did some research and found out that Augusta Avenue is named after Augusta Elizabeth Sullivan (1810-1836), who was the wife of Robert Baldwin (1804-1858), for whom Robert St. is named, and daughter-in-law of William Baldwin (1775-1844), for whom Baldwin St. is named.

Source: Toronto Street Names: An Illustrated Guide to Their Origins by Leonard Wise and Allan Gould, published by Firefly Books, 2000.

While not wishing to distract from the main thrust of this wonderful article I think there is a bit of stretching of the U of T claims. The murky history of medical schools in Toronto shows that the University disestablished their medical teaching in 1850. Trinity, initially established as the Upper Canada School of Medicine may have been where he started. But, was he Anglican enough to sign the statement of faith or did he take the alternate route of graduating from Queen's?

Alice Taylor responds:

Thank you for your query. I will do my best to address your concerns.

First, you are right about the complicated history of Toronto medical schools! I don’t know exactly when Augusta enrolled in medical school only, as I say in the article, that it was in the early 1850s. He had some prior medical training in the U.S. When he was rejected from UPenn on the basis of colour, William Gibson, a professor in the faculty, agreed to work privately with Augusta.

So he came to Canada with a lot of medical knowledge under his belt. And as I say, there doesn’t appear to be any record (at least none that I could find) that says when Augusta enrolled in medical school, so I guess it is possible that he started at the Upper Canada School of Medicine. He is listed as a Trinity student in the 1853-54 medical school circular and graduated with an MB from Trinity. And because after 1853, the proprietary medical schools didn’t have the power to issue degrees, the University of Toronto retained the right to give the exams and confer medical degrees so that, as I understand it, Augusta’s medical degree technically came from U of T. (John McCaul, U of T’s second president claimed Augusta when he gave his testimony to the Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission in 1864.)

Augusta then spent several years practicing in Toronto. Augusta’s listed under Physicians and Surgeons in the 1859 Toronto city directory (and likely earlier directories as well) and is listed with his MB after his name in several Globe newspaper articles.

As to the Anglican question, it is very possible that Augusta was Anglican, or at least worshiped as an Anglican while he was in Toronto. His colleague and close friend Anderson Abbott (a black Canadian who also graduated from medical school in Toronto) was Anglican as were many black Canadians in this period. Augusta was a member of the AME church in Washington, which although Methodist, operates under an episcopal form of church government.

Also, it seems that the requirement that Trinity medical students swear an allegiance to the United Church of England may only have been instituted after 1853, when the competition from other medical colleges eased. A Globe article from March 1853 states that, “The authorities have only lately announced the terms upon which they would grant the degree of M. B.” The article goes on to list the new terms, which includes students declaring “themselves bona fide members of the of the Church of England.” It then says, “it is somewhat strange that this announcement by the authorities of Trinity took place immediately after the second reading of the University bill. After the destruction of the Medical School, Trinity College had no more to fear, and could safely impose upon its students any test, however stringent.”

Citations are available: email alice [dot] taylor [at] utoronto [dot] ca if interested

I read with interest this article and the comments thereon.

Yes, the history of medical education in Canada West/Ontario in the 19th century is indeed murky, but it is reasonably well documented in the records in the University of Toronto Archives, Trinity College Archives, and other places.

When the University of Toronto was established in 1850, it inherited the medical faculty of its predecessor, King’s College, and built a new building (later called "Moss Hall”) to house it. The faculty lasted only three years because the premier of the day decided that the professional faculties (medicine and law) had no place in the university, ostensibly for financial reasons though the immediate reason was the threat of John Rolph, head of the rival Toronto School of Medicine, to bring down the government. The University of Toronto Act of 1853 created two bodies, University College as a teaching body and the University of Toronto as a degree granting institution, which included medicine and law. This arrangement lasted until 1887.

When Alexander Augusta arrived in Toronto from Norfolk, Virginia, he had the choice of attending either the Toronto School of Medicine or the medical faculty of Trinity College. He chose the latter and, in the only faculty circular with students listed, is recorded as being a student during the 1854-1855 session. In the summer of 1856 both the Toronto School of Medicine and the medical faculty at Trinity collapsed, with the faculty of the former resigning en masse and taking over the School from Rolph. The latter was not revived until 1871, following the death of John Strachan, whose interference had caused its demise. Information available in the U of T Archives suggests that Augusta received his MB (Bachelor of Medicine) from Trinity in 1860, just before he is thought to have returned to the West Indies.

Harold Averill

Assistant University Archivist

U of T Archives and Record Management Services

Alice Taylor responds:

Thank you so much for laying out the history of medical education in Canada West/Ontario in the 19th century. I’ll be sure to come to you with any future U of T history questions!

With respect to Augusta, I managed to track down three Trinity Medical College circulars published in 1853, 1854 and 1855. The latter two include student names. As you say, the 1855 Circular lists Augusta’s hometown as Norfolk Va. However, the Circular published in 1854 lists it as Philadelphia Pa. This perplexed me, but I think Augusta likely came to Toronto from Philadelphia (he’d been studying medicine privately in Pennsylvania) but he was born Norfolk, so that is probably why it’s listed the following year.

And thank you for taking the time to let us know that Augusta graduated in 1860, not 1856 as originally stated. We’ve made the correction. I paid a trip to the Trinity archives but not U of T Archives (which I clearly should have done). A little background on why I used 1856. When I was researching the piece I came across conflicting graduation dates for Augusta. However, the vast majority of published sources use 1856 as his graduation year (including the Journal of the National Medical Association’s July 1952 issue that features Augusta on its cover). So do most credible online sources. U of T Faculty of Medicine uses 1856, as does the National Institute of Health. I also found primary sources that refer to him as “Dr. Augusta” as far back as 1857, so he used the title Dr. before graduating with the M.B.—I can only assume standards were different back then. All that to say, because I didn’t have primary sources that confirmed a graduation date, I went with the most credible secondary sources I found.

Glad to set the record straight.

This is such a great article, glad to learn more about black history in medicine

Many thanks, Alice Taylor, for this work. It's historical but still relevant.