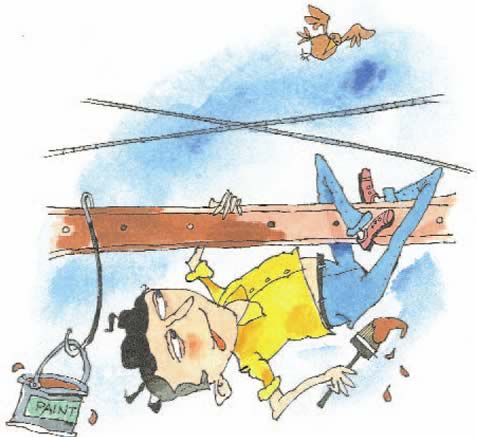

HIGH-WIRE ACT

For several summers in the 1950s, I worked for Ontario Hydro painting electrical towers. We worked in teams of four or five, using lineman’s belts with a safety hitch, and a ring to hold the paint pot. With brushes in hand, we climbed the towers to just below the wires and painted all sides of the steel girders, including the bottoms. The trickiest part was the centre of the girder, because there was nothing to hold on to. Most of us chose to sit on the beam and slide backward as we painted. The braver – or more foolhardy – treated the girder like a tightrope, painting as they walked. Sometimes Hydro wanted the tops of the towers painted. In those cases, we had to put our feet on the power lines to reach the ends of the girders (the electricity was turned off – the lines typically carried 110,000 or 220,000 volts). Thankfully, we never had a single accident or fatality. A fellow painter once froze halfway up the tower, but he managed to get down. Not surprisingly, he found a different line of work.

Wesley Turner

BA 1956 VIC, MA 1962

Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario

OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

As an English literature graduate, my greatest dream was to work in the Canadian publishing industry. Just before graduating, I found what seemed like a promising opportunity in the Toronto Star want ads. I went for a short interview with the TransCanada Readership Service and spoke with Dan, an attractive young man who emphasized the need for determination to make a mark in “magazine distribution.”

The next day, Dan drove me and four other new hires to a high-rise apartment building in Don Mills. As we sat in the parking lot, he gave us a short pep talk about closing techniques. Then we swarmed the building, selling magazine subscriptions door to door. It was an eye-opening and exhausting experience, but it didn’t really fulfil my desire to work in the publishing industry. On the other hand, after four months I had become a successful closer and could talk to anyone about anything without getting the door slammed in my face.

On average, I knocked on about 75 doors a day and sold 12 subscriptions. I may not have realized it at the time, but selling door to door was a life-enhancing opportunity that helped me understand the genuine interests of Joe Public. In those few months, I also discovered a simple truth: if I couldn’t sell, I wouldn’t eat. This was a fundamental survival lesson I never learned in the ivory tower.

Margaret Lindsay Holton

BA 1979 UC

Waterdown, Ontario

SWEPT AWAY

The strangest job I ever took was as a dustherd. The work was actually called “weekend cleanup,” but herding dust is what we did. The job, at a sawmill in Burnaby, B.C., paid a princely $5.10 an hour and made us members of the then-mighty International Woodworkers of America union.

During the workweek, the mill’s complex machinery became coated in sawdust. University students came in on Saturdays to clean it up. We used compressed air blown through rubber hoses tipped with long aluminum tubes. Starting with the highest bolts and frames on the overhead conveyors, we worked down via the saw tables to the floor, piling up the sawdust in Sahara-like dunes until it could be swept down the hopper. Different sizes and shapes of shavings reacted differently to the airstream, so the dustherd always needed to watch for capricious particles escaping to the side.

This experience has stood me in good stead ever since, most notably in managing a laboratory where students and staff have widely varying skills and interests.

Richard Summerbell

PhD 1986

Utrecht, The Netherlands

Share your own story of a strange job in the comment box below