As huge crowds took to the streets in Tehran last year to protest disputed presidential election results, OISE professor Shahrzad Mojab agreed to be a guest on a CBC radio show with Iran’s former queen, on the phone from Morocco.

Mojab had become a political exile shortly after the Iranian Revolution of 1979 − the same revolution that had unseated the queen and resulted in the arrest or execution of many female activists. Now the two women were being interviewed about a new revolution in Iran.

For Mojab, the rallies following last year’s election brought back memories of her own political activism. In an essay, she wrote that the footage of Iranian women protesting had reignited her sense of personal pride: “The images of young Iranian women battling police or even their sheer presence on streets disrupted the image of ‘Muslim’ women as passive, home-bound and wrapped in her symbol of oppression – the veil.”

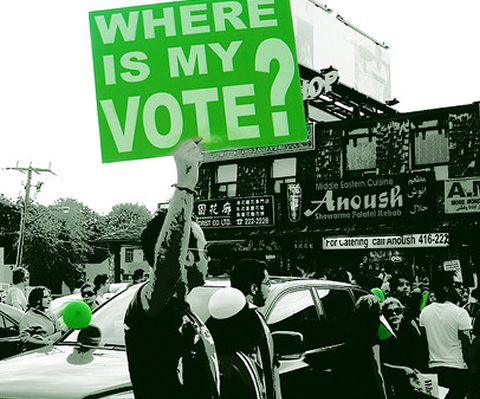

Many young Iranians in Canada felt strongly about the importance of last year’s election, believing that a significant turning point in their home country was at hand. Students from U of T, Ryerson University, and York University rented six buses and took about 200 people to vote at the Iranian embassy in Ottawa. They advertised on campus and went to Khorak Supermarket, a popular Iranian plaza in North York, to invite other members of the community to go with them.

Ahmad Shahroodi, who is working on his master’s in civil engineering at U of T, drove to Ottawa to vote with four friends. Like many others, he was shocked when Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was declared the victor with 63 per cent of the vote. “[Initially,] Tehran was completely silent. No one knew what to do,” said Shahroodi. “The second day, people started talking: ‘Let’s make an assembly out of all the candidates and recount the votes.’ But they rejected the proposal. They opened a few ballot boxes in front of the media…”

In the crackdown that followed the peaceful rallies, at least 30 people were killed and more than 1,000 arrested. Some protesters received long prison sentences; others were executed. The opposition called off rallies to mark the first anniversary of the protests after threats and pre-emptive arrests. Despite these setbacks, some U of T students and faculty from Iran say they remain optimistic that the movement for greater freedoms has taken root in the hearts and minds of a newly politicized younger generation.

Significant change will take time, though. Amir Hassanpour, a professor in U of T’s Department of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, says the Iranian opposition leader, Mir-Hossein Moussavi, fell short of advocating radical political change. “[Moussavi] had an agenda of sharing power with Ahmadinejad’s faction. Even if he had full power in replacing Ahmedinejad, there would have been certain legal reforms − minor changes, less pressure on women in terms of veiling − but no constitutional reform.”

Hassanpour is critical of the reformist “green” movement, since it would maintain Iran’s theocracy. He advocates replacing the theocracy with a secular and democratic regime, which he believes only Iranians working for change in Iran can achieve. “Many intellectuals in North America are actively engaged in the politics of reforming or ‘greening’ the theocracy rather than getting rid of it,” he says. “In doing so, I think they are acting against the interests of not only Iranians but also people throughout the world who are suffering from religious fundamentalism and theocratic rule.”

Ramin Jahanbegloo, a U of T political science professor who was detained in solitary confinement for four months in Iran’s Evin prison, believes the younger generation will eventually usher in change in Iran. “They have now more inclination towards ideas like human rights, political accountability, and transparency,” he says. “Iran is maybe the only country in the Middle East which has the potential for democracy. It has a young population, but also a highly educated urban population.”

Ongoing, non-violent action will be crucial to keep up pressure on the administration, says Shahroodi. Ahmadinejad visited Tehran University this past May. “He didn’t announce the visit, he did it quietly,” Sharoodi observes. “After a while students saw him, told others, and started protesting. He left. He left quickly. The questions are still alive.”