What Is the Future of Urban Farming?

Researchers at U of T Scarborough are testing which crops fare best on city roofs Read More

Toronto has one of the most progressive green roof policies in North America – and was the first city on the continent to make them mandatory for new construction. Green roofs help cool buildings, leading to lower energy costs.

There are currently more than 700 dotting the city but most use shallow substrates (a mix of organic material, crushed bricks and some minerals such as sand and shale) instead of soil – and little to no irrigation. They require minimal maintenance and have not been designed with farming in mind.

“Growing food in these conditions is not easy,” says Marney Isaac, a professor in the department of physical and environmental sciences at U of T Scarborough who is co-leading a project with Scott MacIvor, an assistant professor in UTSC’s department of biological sciences, to test whether these roofs can become food-growing gardens.

Isaac, who is an expert on plant-soil interactions and sustainable agriculture, says a major challenge is making sure the crops get enough nutrients. Since the typical green-roof substrate is not as nutrient-rich as soil – and dumping loads of fertilizer on the tops of buildings isn’t possible – the team is testing a type of organic fertilizer.

Heat (too much) and moisture (not enough) are also concerns. Most Toronto green roofs are planted with sedum, a durable and drought-tolerant type of succulent that is efficient at storing water and cooling the soil. The researchers are looking at how different species of sedum might help more sensitive plants, such as crops, grow in harsh conditions.

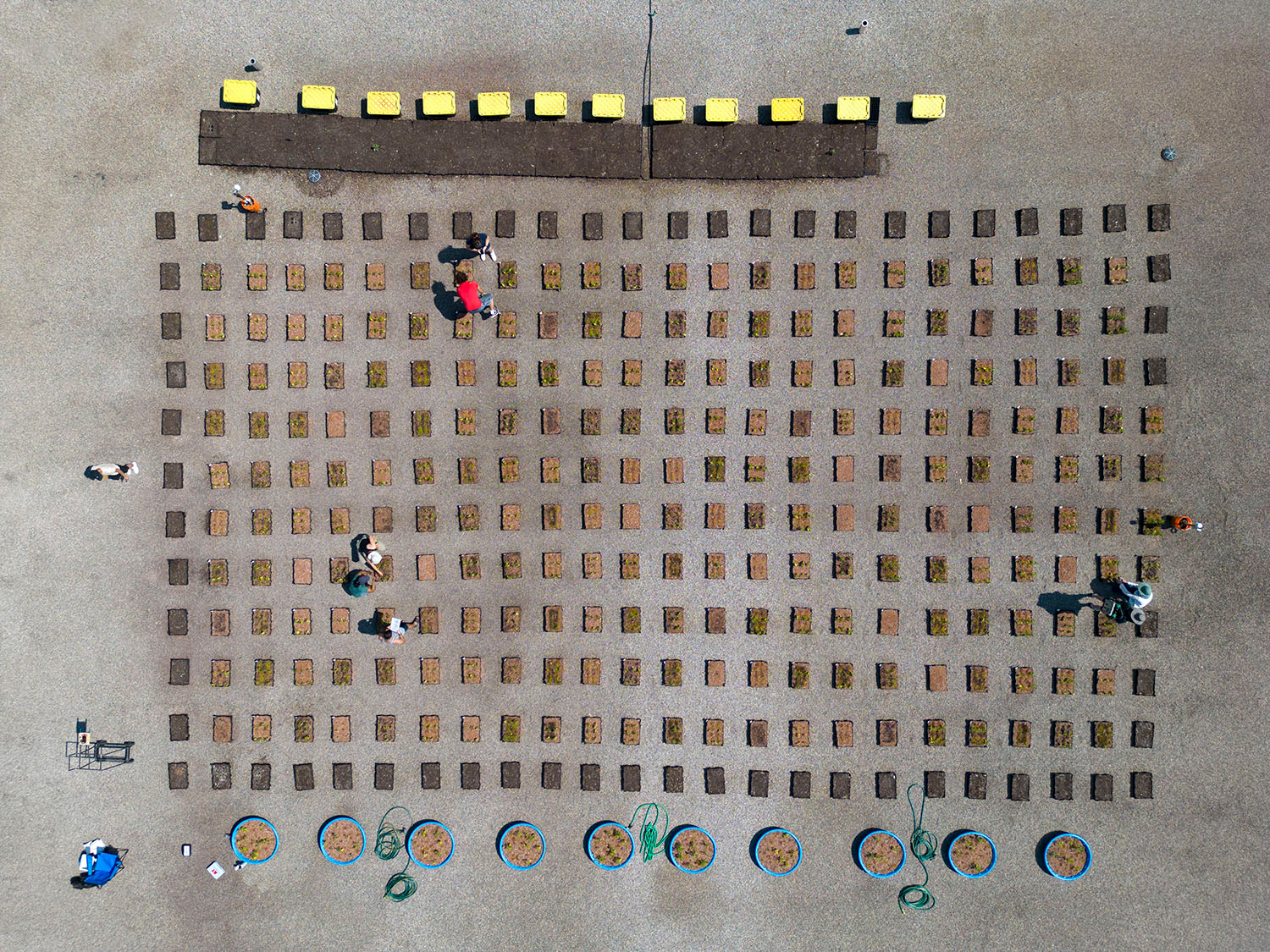

The researchers are currently growing a variety of crops in 400 individual modules – boxes measuring 60 centimetres by 40 centimetres – on the roof of Highland Hall at U of T Scarborough. The goal is to see how certain plants interact with each other – a tried-and-true farming process known as intercropping. For example, planting legumes contributes nitrogen to the soil, which supports the growth of other crops.

It’s possible that one day your local grocery store will be able to grow food on its roof. Or people living in condos and apartments will be able to ascend a few floors to harvest their own fruits, vegetables and herbs, including ones not commonly stocked in stores. “It could give people living in cities an opportunity to grow the types of culturally important foods they can’t easily get,” says Isaac.

No Responses to “ What Is the Future of Urban Farming? ”

Shiri Rosenberg (MBA 2004) writes:

I thought your readers might be interested in a complementary article about an urban farming project we at Colliers Real Estate Management Services have launched at many commercial office towers in Toronto, including at Royal Bank Plaza and 150 Bloor Street West, at Avenue Road.

Gwen Farrow (BA Victoria 1959) writes:

Our roof in Scarborough is 21 storeys high, so subject to wind challenges. But we have learned what crops do best. We are lucky that our roof can support raised beds with wooden sides and real soil. Two hoses are available and gardeners supply their own tools and crops. I have many flowers plus strawberries, peas, radishes, carrots and tomatoes. Other gardeners have had successful projects, too. Green roofs can work; we've proved it for over 40 years!

Readers might also be interested to see other projects across the country. For example, the IGA store in Montreal that has an organic rooftop farm:

https://livingarchitecturemonitor.com/articles/award-winning-iga-organic-rooftop-farm-sp22